Hospital PICC IVs can pose blood clot risks

Check in to a hospital, whether for illness or tests, and an IV is almost sure to appear. They’re everywhere, delivering fluids and potentially live-saving drugs to patients.

Check in to a hospital, whether for illness or tests, and an IV is almost sure to appear. They’re everywhere, delivering fluids and potentially live-saving drugs to patients.

The “normal” IV, called an intravenous catheter, delivers medicines into a vein near the skin surface. It can be safety left in place for 3-4 days.

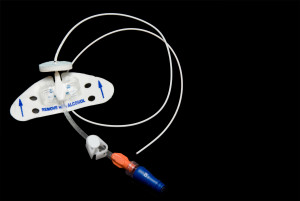

If the treatment must go on for longer—for example, chemotherapy or long-term antibiotic or cancer treatment, hospital sometimes use a PICC line (peripherally inserted central catheter), photo above. With proper care, the PICC line can be left in place for months.

According to Vineet Chopra, University of Michigan assistant professor of Internal Medicine and a leader of a recent study, PICCs are much easier to use than normal IVs. Because PICCs can stay inserted for longer than other IVs, Chopra said patients can go home with them, resulting in less time in the hospital and added convenience for the patient. Furthermore, PICCs can reach all the way to the heart, whereas normal IVs end in the arm.

But PICC lines pose a risk for blood clots that can be especially severe for patients who have already had clotting problems.

In a recent study by the University of Michigan, almost 30 percent of patients with PICC lines developed blood clots. Patients who had any kind of surgery during their hospital stay, or had had any kind of deep clot in their medical history, were more likely to get a DVT (deep vein thrombosis) associated with their PICC.

The results, says Chopra, suggest that doctors should use PICCs only when they really need them – and that they should tread carefully when considering PICCs for certain patients, monitor for clots, ensure patients continue taking aspirin and statins that they were already on, and take the PICC out before any operation.

Patients should feel empowered to ask what kind of IV device they’re getting, and what risks it carries, before one is placed, he says. Once a patient has a PICC, it’s important that they know what symptoms might indicate they have a clot – and to ask when the PICC can come out.

I’m glad to know this. As an APS patient with a history of blood clot in the brain, I want to reduce my risk of clots any way I can. That means avoiding PICC lines unless they’re absolutely mandatory. And if I’m ever forced into a PICC line, I’ll know to make sure my medical team is extra vigilant in clot prevention.

For more information about the University of Michigan Study, look here: http://bit.ly/1FMyo6I